Girls’ Education in Afghanistan: Progress and Challenges

In this NORRAG Highlights, Yixin Wang, an education data consultant focusing on topics such as data-driven policymaking to achieve inclusive, equitable, and quality education for all, discusses the education system in Afghanistan in light of the recent US withdrawal. She discusses the challenges that the Afghan education system faces, as well as the barriers to education that girls face specifically.

The recent US withdrawal from Afghanistan stirs up extensive concerns, especially on women and girls’ rights. Standing at a turning point in history, it is critical for Afghanistan and the international community to work together to keep progressing its education system. To this end, this post aims to provide a broad scoping overview of the progress and challenges in Afghanistan’s education system.

Conflict-affected for four decades, the education system in Afghanistan is highly fragile. While many countries have achieved universal primary education, this basic goal is still distant for children in Afghanistan. According to UNICEF, the adjusted net attendance rate for primary school is 64 per cent in Afghanistan or lagging 23 percentage points behind the world average. Moreover, the gap persists at lower and upper secondary levels, suggesting many school-age children are excluded from receiving formal education.

Girls remain particularly marginalized throughout all levels of education. Data from the 2015 Afghanistan Demographic and Health Surveys indicate that nearly half of girls between the age of six and eleven are out of school. This figure is six percentage points higher than the out-of-school rate among children from the poorest wealth quintile. In addition to existing challenges, 10 million learners’ education in Afghanistan has been disrupted due to the COVID-19 school closures. As of September 2021, the total duration of school closures, including full and partial closures, has been over 44 weeks in the country. This prolonged schooling disruption can profoundly affect children’s education trajectories, increasing the likelihood of dropping out when schools do reopen.

How far has Afghanistan come along in the past decades?

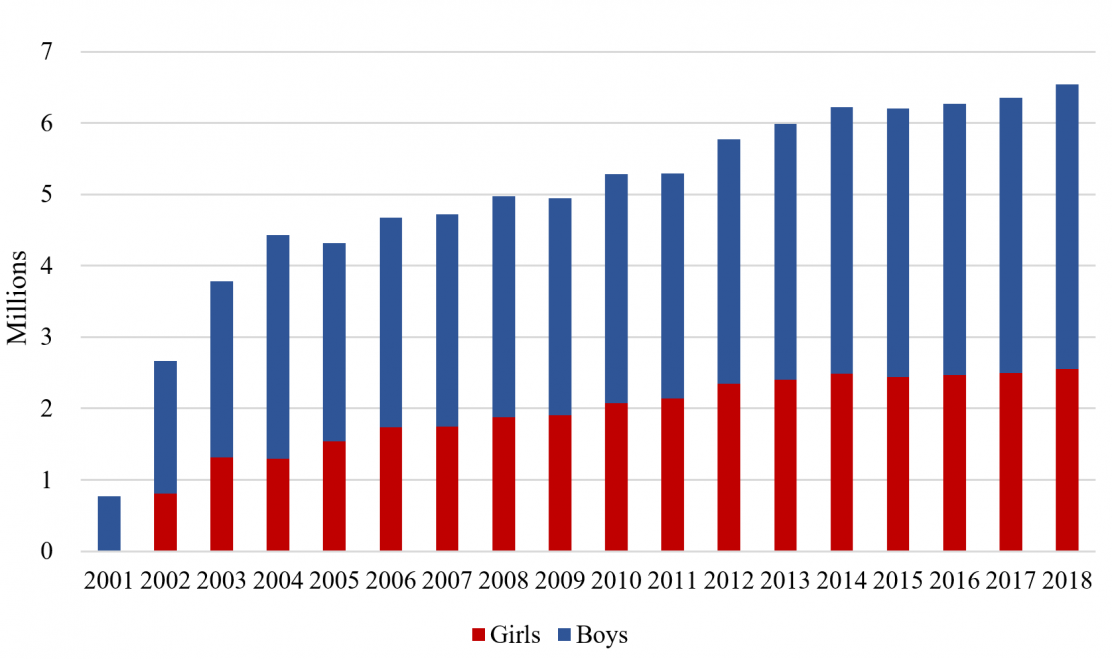

Based on the Afghanistan Ministry of Education Annual Progress Report in 2020, nearly 10 million children falling between primary to tertiary school-age are enrolled. This number had increased ten-fold compared to that in 2001. Among these 10 million learners, approximately 40 per cent are girls. Compared to 20 years ago, this is tremendous progress, especially at the primary level, where the most growth is observed (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Number of primary school enrolment in Afghanistan by sex, 2001-2018

Source: UNESCO Institute of Statistics

The rapid growth in enrolment is paired with a sharp increase in the number of schools and teachers. According to the UNESCO Institute of Statistics, the number of schools increased from 6,000 in 2001 to nearly 18,000 in 2018 and the number of teachers increased from 27,000 in 2003 to nearly 226,000 in 2020. Many of these schools are considered Community-Based Education (CBE) that offer instruction close to their communities for children in grades one to three. This CBE approach makes everyday transportation between home and school much easier and significantly extends their learning opportunities.

What are some unresolved challenges in Afghanistan’s education system?

All of these achievements have significant implications on both the future for individuals as well as the country as a whole. On an individual level, effective education can build a solid foundation and open avenues for future success. At the national level, prevailing evidence points out the positive relationship between education, socio- and economic- development. However, these accomplishments should not mask the deep-rooted challenges facing Afghanistan’s education.

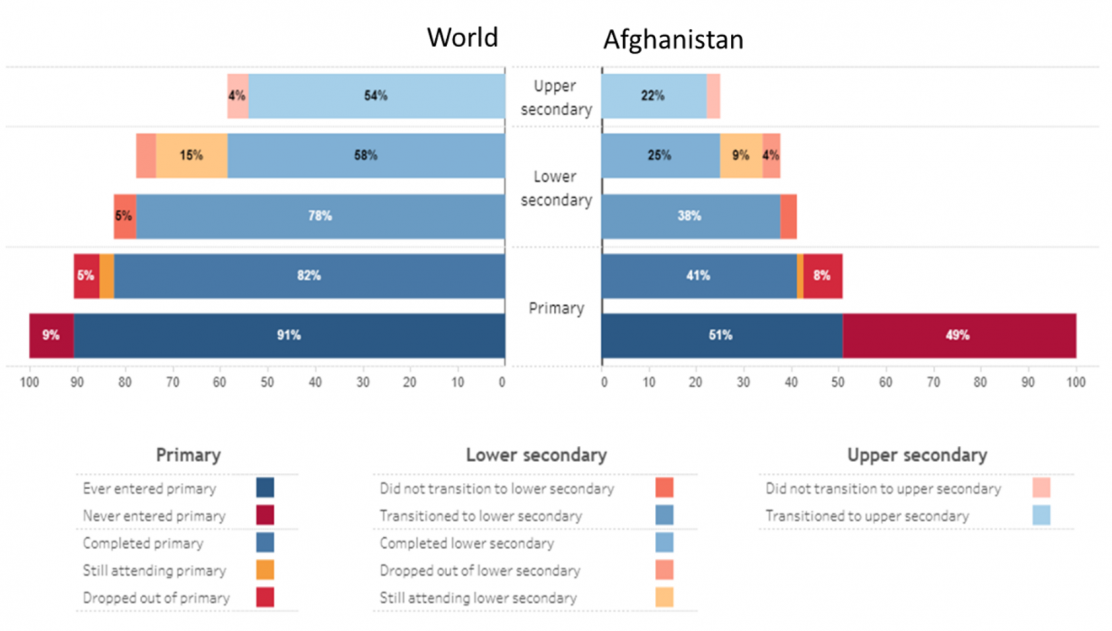

Although much progress has been made in girls’ education, it still lies at the heart of all these challenges. A recent UNICEF report exploring the education pathway in 103 countries and territories finds that while only 9 percent of the girls of upper secondary school age never entered primary, an astonishing 49 per cent of girls in Afghanistan never entered primary school (see Figure 2). This disadvantage in girls’ education is compounded throughout the education system, as only one in five girls of upper secondary school age successfully transits to upper secondary school.

Figure 2. Education pathway analysis, a comparison between world average and Afghanistan girls

Source: UNICEF report on education pathway analysis

Lower education attainment among Afghanistan girls translates to lower skills level. According to the most recent data available on United Nations Global SDG Database, only 22 per cent and 25 per cent of students in Afghanistan achieve the minimum proficiency in reading and mathematics by grade three, respectively. When it comes to youth literacy rates among young people aged 15-24 years, nearly 45 per cent of the girls remain illiterate, meaning that nearly half of young girls cannot read or write a short and simple statement about their everyday life. This early disadvantage in foundational skills development carries along to their early adulthood, as International Labour Organization reported a staggering 80 per cent of the young females aged 20 to 24 as not being in employment, education, or training.

Barriers to education for girls in Afghanistan

Worryingly, socio-cultural norms in Afghanistan do not support girls to receive education or pursue work. Data from the Afghanistan Living Conditions Survey 2016-17 shows that among all reasons preventing girls from getting an education or participating in societal activities, family disapproval is one of the most prominent. In addition, a joint report published by UNICEF and UNGEI finds that over one-third of the girls aged 20 to 24 reported being married before their 18th birthday. The report also finds that a higher share of girls than boys are engaged in child labour, further impeding their educational prospects.

Even when girls do attend school, many schools remain unaccommodating for girls to thrive. For instance, more female teachers could serve as role models for many girls and consequently increase the likelihood of girls attending school. Although the share of female teachers has grown substantially to 36 per cent in primary education, this number is much lower in the remote and rural areas, where the girls are more excluded from formal education. A UNICEF and Emory University joint report in 2009 finds that, among 7,769 schools in 24 provinces, only 22 per cent of the schools had installed separate toilets for girls and boys. The lack of access to clean and private toilets in schools can disproportionally affect girls, especially when girls reach puberty and begin menstruation.

What does the future hold for education in Afghanistan?

A combination of prolonged conflicts, an unstable political environment, and the COVID-19 pandemic introduced significant uncertainties in Afghanistan today. In terms of the educational resources and facilities, many schools are under re-construction due to ongoing fragility and conflict. A new layer of complexity added by uncertainties of U.S. withdrawal will inevitably make the already limited educational resource scarcer, and potentially exclude the most vulnerable groups from an opportunity of receiving education. In addition, uncertainties around the future of Taliban’s education policy also introduce considerable complication towards girls education. Particularly, should the Taliban ban co-educational classrooms and enforce instructional segregation by gender, the education system can be further stretched.

Finally, uncertainties in international aid that is conditional on collaboration with the new government may put the education system in Afghanistan at risk. Donors have indicated they will send humanitarian aid, but the international community will need to find a way to fill the void concerning education and engage with the Taliban government meaningfully. In addition to improving access and quality of education, concerted efforts should improve girls’ participation in all levels of education. Without call-to-action and collective efforts among international communities and local educational agencies, two-decade progress in girls’ education can be quickly undone. Millions of girls’ futures are at stake, and the price of failing them is dear.

About the author: Yixin Wang is an education data consultant working on data and analytics. Her work focuses on data-driven policymaking to achieve inclusive, equitable, and quality education for all.

View this post on the NORRAG Blog at this link.